|

SEA DIAMONDS

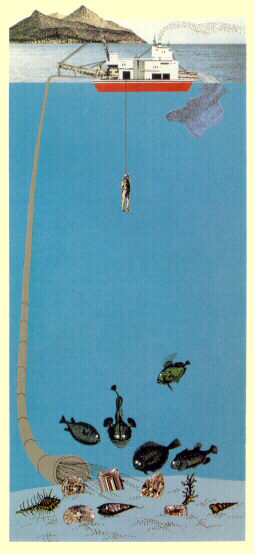

An enterprising Texan called Sammy Collins drew worldwide attention in 1962 when he announced that he'd recovered 50,000 carats of diamonds worth $1.5 million from the seabed off the treacherous Diamond Coast of South West Africa.

Collins figured that since diamonds had been found in abundant amounts along the coast, most likely carried there by the Vaal and Orange rivers from some far inland deposit, they also ought to be found under the ocean.

An enterprising Texan called Sammy Collins drew worldwide attention in 1962 when he announced that he'd recovered 50,000 carats of diamonds worth $1.5 million from the seabed off the treacherous Diamond Coast of South West Africa.

Collins figured that since diamonds had been found in abundant amounts along the coast, most likely carried there by the Vaal and Orange rivers from some far inland deposit, they also ought to be found under the ocean.

Over a period of three years, Collins used the equivalent of huge vacuum sweepers to suck some 400,000 carats of diamonds from the seabed. His adventures set off a mini-rush by others to try this new type of exploration but terrible working conditions and uncertain diamond deposits sent most into early obscurity.

Today, with improved technology, De Beers and others are once again probing the waters of the South Atlantic, bringing closer the prospect of viable undersea diamond recovery in the 1990s.

LET THERE BE LIGHT -AND FIRE

The time and place: 1919, London, the British Imperial capital city, still rejoicing over Germany's defeat in the Great War ended the previous fall.

The man: 21-year-old Marcel Tolkowsky, a student in mechanical engineering and son and grandson of Antwerp diamond cutters.

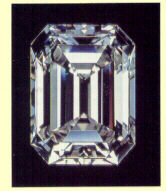

The event: Creation of a new diamond cut designed to release the maximum "fire" from the heart of the stone. Young Marcel had just etched his name into diamond history with his design of the Tolkowsky cut or, as it's more often called today, the Ideal cut.

We're talking about what many experts consider the most critical of the diamond's often-discussed 4 C's - cut, clarity, color and carat weight (more on the final three later).

Cut is what turns an opaque, dullish-gray pebble into a mirror of light. In its ultimate form, a finely-shaped diamond is a masterpiece of mathematics, its angles precisely drawn. In a classic cut, each of the 58 facets is aligned in exact relationship to the others to achieve maximum beauty.

This is the beauty seen across a dance floor or a dining room as a

brilliant flash of light, alive with a rainbow of changing colors. It's what sets the diamond apart as the paragon of gemstones. It's what makes the diamond so special, so valued.

Achieving this goal took thousands of years.

Cut is what turns an opaque, dullish-gray pebble into a mirror of light. In its ultimate form, a finely-shaped diamond is a masterpiece of mathematics, its angles precisely drawn. In a classic cut, each of the 58 facets is aligned in exact relationship to the others to achieve maximum beauty.

This is the beauty seen across a dance floor or a dining room as a

brilliant flash of light, alive with a rainbow of changing colors. It's what sets the diamond apart as the paragon of gemstones. It's what makes the diamond so special, so valued.

Achieving this goal took thousands of years.

The first crude attempts to improve on nature were made in India, where it was discovered that diamond, like wood, possesses a grain and that diamond can be split or cleaved along that grain. The Indians also discovered that when two diamonds are rubbed together some of the surface of each stone will be chipped or worn away- and used this technique to give some spark and life to the rough stones.

It took many years and European know-how to move cutting beyond the state of wonder to the state of beauty.

Progress was marked by three watershed events: the late 15th century discovery by Louis de Berquem of how to use a wheel impregnated with diamond dust to polish a diamond (the concept is still in use today); the 17th century invention, by a Venetian lapidary named Vincenti Peruzzi, of a 58-facet cut, ancestor of today's popular brilliant cut; and the 18th century discovery (inventor unknown) that a diamond could be sawed. Until then, unwanted portions of a stone had to ground away, causing tremendous loss.

The cutter's art is designed to make the maximum use of light. Put simply, a brilliant-cut  diamond takes in light, bends the

rays, bounces them around within the stone, and then ejects them broken into the colors of the spectrum.

diamond takes in light, bends the

rays, bounces them around within the stone, and then ejects them broken into the colors of the spectrum.

Just how light is broken up depends on minute differences in how a diamond is cut. A lot of differing opinion is centered on how wide the table (the flat top surface of the diamond) should be. Those who swear by the Tolkowsky or Ideal cut say the table should be 53% as wide as the overall width of the stone at its widest point. Others favor a table somewhere between 57% and 65%.

It all really comes down to a balance of "fire" versus "light." The Tolkowsky backers say his cut does a better job of breaking down light into the entire spectrum, sending back a shining rainbow of colors from the diamond. They glory in this "fire." Those favoring a wider table insist that their cut allows the diamond to return much more "light"-as much as five times more than the Tolkowsky. This brilliance, they say, is especially stunning when seen from an angle, and that's how most people see a diamond. Personal preferences will decide which diamond a person buys. What's really important is to understand what a critical difference cut can make.